- Home »

- September 2022 »

EXPERT EXPRESSIONS

Corporate Governance Demystified

September, 2022

ACT IN HASTE; REPENT AT LEISURE

M. Damodaran

Chairperson, Excellence Enablers

Former Chairman, SEBI, UTI and IDBI

Decades ago, the largest public sector banks were nationalised, in two tranches. It was justified as a reform measure, replacing creditworthiness of the person, with creditworthiness of purpose. Is it right to revert to complete privatisation of the banking sector, in the name of reform?

A few months after the financial meltdown of 2008, a football match between Manchester United and Newcastle United took place in England. As matches go, the quality of the game was nothing much to write home about. What was significant was that Manchester United had the logo of AIG, and Newcastle United had the logo of Northern Rock. Weeks earlier, AIG had effectively come under the US Government control, and Northern Rock was taken over by the UK Government, following its difficult financial circumstances. As one wag observed, this was an international match between the USA and England, going by the sponsor logos on the shirtfronts. It mattered little to many people that the problems of these two sponsor institutions had led to many people losing their shirt.

One was reminded of this story in the context of the now-on-now-off discussions regarding public sector ownership of banks. Those who fly the flag of privatisation, continue to believe that it is the answer to all problems that the economy faces from time to time. At the other end of the spectrum, there are those that believe that public ownership of banks is a continuing necessity, especially in an economy with wide disparities, and an extremely heterogenous set of consumers.

For a couple of months, the subject of privatisation of banks appeared to have been put on the backburner. Then an article, co-authored by Herwadkar, Goel and Bansal, all from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), made out a case for a phased privatisation of public sector banks (PSBs) as a more desirable option, than rushing into depriving Government of its ownership in all PSBs. Given that the Government had, from time to time, been making statements about succeeding rounds of privatisation of all PSBs (except State Bank of India), this article seemed to be going against the grain, coming as it did from three researchers of the Central Bank. Sufficient hackles must have been raised for the Central Bank to come out with a communication titled “RBI clarification” on August 19, 2022, reiterating that the alternate perspective propounded by the three researchers was, as already stated, their view, and did not represent the views of the RBI.

Now that the possibility of a conflict between the Government and the RBI, on this account, has been laid to rest, it is time to look at the substantive issue involved. In a climate in which reform and privatisation are erroneously treated as synonyms, it must have taken some courage to canvass the proposition that rushing into privatisation is not what the banking sector requires at present.

Before getting into the relative demerits and merits of Government ownership of PSBs in India, it is necessary to take note of the fact that post the financial meltdown, many developed countries nationalised some stressed banks, and some infused enormous amounts of capital to meet bank-specific needs. It became abundantly clear that public ownership of banks was nowhere near its sunset.

Following a few mergers, the number of PSBs in India has significantly reduced. More importantly, the remaining PSBs have acquired a scale and a size which ensures that they are no longer pushovers in this sector. With close attention, and with institutions to which they could transfer their stressed assets, the remaining PSBs have significantly cleaned up their books, and are in a position to better meet the banking needs of their diversified clientele.

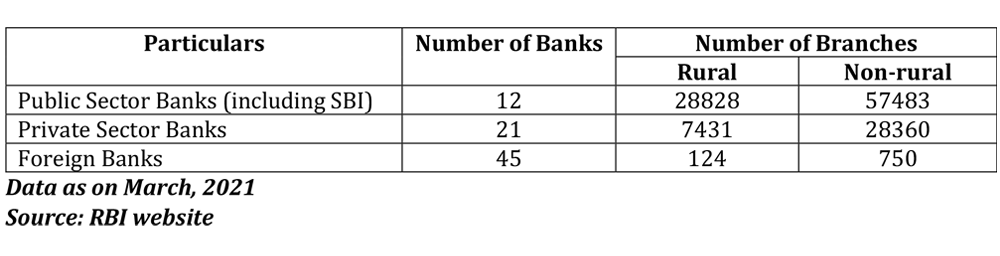

Consequent on the nationalisation of banks in 1969 and in 1980, banking facilities have been taken to areas, and to people who had no access to them. This act of inclusiveness has helped to foster a sense of belonging, as well as to empower those who had hitherto been denied banking services, to ask for products and services that they did not even know existed. In this aspirational endeavour, the private sector banks have had little, or no role. Most of the large number of new bank accounts that have been opened in the last few years, have been opened by PSBs. With their stipulations of minimum balances, which prima facie seem unreasonable, private sector banks have stayed out of this area of activity. When it comes to sectoral interventions such as agricultural credit, there is comparatively insignificant contribution from private sector banks. Further, as the article under reference conclusively establishes, the mandated priority sector lending targets have been met by private sector banks by acquiring assets from NBFCs and other entities. The degree of involvement in assessing credit needs, interacting with borrowers, ensuring timely access to inputs, and supporting the marketing efforts, have not been concerns that have unduly bothered the private sector banks.

There are economists, especially those residing outside India, including some with a text book knowledge of so-called Indian ground realities, who believe that the PSBs are inefficient, and therefore have no right to exist. They see this through the lens of profit maximisation, consistent with the Milton Friedman model that shareholders should be looked after, and other stakeholders can fend for themselves. Efficiency should also be seen in context. The PSBs came into existence long years before the internet, and therefore they have significant brick and mortar presence spread throughout India. The private sector banks, that came in subsequently, do not have this burden from the past. Further it is well recognised that efficiency is not a function of ownership. Therefore, to subscribe to the view that public sector ownership will necessarily translate to inefficiency and suboptimal performance is an erroneous conclusion. Banking is also an expression of confidence. Subsequent to the 2008 crisis, many depositors sought comfort in the Government ownership of PSBs, and did not wish to expose themselves to the uncertainties that a challenged private sector bank could bring into their lives. Also, every conceivable poverty alleviation scheme, with a credit input, has been significantly contributed to by PSBs.

When the then largest private sector bank was experiencing a run, it was to the State Bank of India that it reached out for help. Even at the risk of exaggeration, it should be pointed out that individual acts of greed and misdemeanour have brought some private sector banks, both big and small, to their knees. On the other hand, many of the problems that PSBs face are a result of the prodding by the Government to lend to infrastructure projects, as well as on account of judicial decisions that have, in spite of good intentions, transformed seemingly creditworthy risks into completely unacceptable propositions. Private sector banks have had a much lesser problem on account of these externalities.

India, it hardly needs to be said, is as heterogenous as a country can get. There is every conceivable divide that separates some segments of the population from some others. In such a situation, to have only private sector banks, with profit maximisation and increase in market cap as the guideposts, is a sure recipe for disaster. PSBs must not only be allowed to remain in existence, but should be strengthened, and encouraged to play a legitimate role that less advantaged sections of society need the banks to perform. PSB leadership, as we have argued earlier, should be sufficiently empowered and incentivised to provide the kind of leadership that large organisations require, especially when there is a significant public responsibility to be discharged. Tying them hand and foot, and expecting them to compete, is worse than comparing apples with oranges. PSBs must have Boards that lead, and not Boards that are led. Periodic discussions on privatisation of PSBs, accompanied by trashing them in public fora, has an avoidable negative impact on the morale of the workforce.

Private sector banks have a legitimate role in a growing economy. However, they should supplement, and not supplant, PSBs.

In good times there can be academic debates on whether privatisation is the panacea for all ills. But as we have seen, in bad times, it is to PSBs that the less affluent flock, in search of safety and security.

Dukh me sumiran sab kare, sukh me kare na koi,

Jo sukh main sumiran kare, Dukh kahe ko hoye. (Kabir)

Tailpiece: Responding to a query on high charges by a member of the RBI’s Taskforce on Customer Service a decade or so ago, a legendary private sector bank chieftain said “You cannot get 5-star food at Udupi hotel rates.” He did not perhaps know that, more often than not, Udupi hotels serve better food. Some food for thought.

THE STORY SO FAR…

Excellence Enablers

Corporate Governance Specialists | Adding value, not ticking boxes | www.excellenceenablers.com

(292KB)

(292KB)