Corporate Governance Demystified

February, 2022

JUDGE RIGHT THAT YE BE JUDGED RIGHT

M. Damodaran

Chairperson, Excellence Enablers

Former Chairman, SEBI, UTI and IDBI

The faith and trust that affected persons place on every forum that pronounces on every disputed case has to be matched by continuing efforts made by that forum to ensure that justice is dispensed in every case that comes up before it. Therein lies hope for those that seek justice.

It is not unusual for appellate authorities to set aside findings of lower Courts and Tribunals, and, in the process, express righteous indignation at the manner in which, and the dilatoriness with which, the facts and issues have been dealt with. Notwithstanding the competence, and the care and caution, with which the original forum might have arrived at its decisions, there is always the possibility that the appreciation of evidence, and the findings arrived at, could be erroneous. It is to address this possibility, that appellate fora exist. Scrutiny of facts and arguments by the appellate fora could lead to validation of the conclusions arrived at, in the matter before it in appeal, or setting right the mistakes and inadequacies that have crept into the original order.

The history of decisions in the area of securities law in India is not wanting in an adequate number of instances in which the appellate authority has either set aside, or remanded for fresh consideration, a matter that has come up before it in appeal. Ordinarily, this should be treated as par for the course, and should not give rise to disproportionate comment or concern. However, when three orders of the Securities Appellate Tribunal (SAT), in a short period of time, not only reject the findings of SEBI, but also contain strong indictments of the officials that passed those orders, it is time to sit up and take notice. There are perhaps inherent systemic flaws that might need to be addressed if the recent strong observations of the appellate body are not to manifest themselves time and again.

First, the specifics. In an order passed on 20-12-2021, SAT held, applying the principle of res judicata, that an order passed by a Whole Time Member (WTM) of SEBI was “wholly without jurisdiction”. The Tribunal went on to add that “the contention of the respondent that the said direction was issued only in pursuance of direction issued by this Tribunal is patently erroneous.” Not satisfied with these observations, the Tribunal went on to state “In a country governed by the rule of law, the finality of a judgement is absolutely imperative and great sanctity is attached to the finality of the judgement… Issuance of a fresh show cause notice leading to the passing of the impugned order is not only abuse of process of the court (emphasis supplied) but has far reaching adverse effect in the administration of justice as held by the Supreme Court in….” Allowing the appeal, the Tribunal ordered the payment of costs by SEBI to each of the appellants in this matter.

In a matter decided on 23-12-2021, while dealing with a case in which there was an inordinate delay in the issuance of the show cause notice, the Appellate Tribunal did not view with favour the act of the Adjudicating Officer in “skirting the issue and pushing it under the carpet without dealing with it”. The Tribunal noted that some of the grounds raised in appeal had not been dealt with by the Adjudicating Officer, and characterised it as amounting to judicial indiscipline (emphasis supplied). In this case too, while deciding the impugned order, the Tribunal allowed the appeal with costs.

In yet another order, the Tribunal stated that the Adjudicating Officer had dealt with an issue in a very casual manner and that “prima facie in our view this amounts to judicial dishonesty” (emphasis supplied).

The findings that the orders passed suffer from judicial indiscipline, and dishonest conduct, do not show in good light the authority which passed the original orders. While it is possible to take sides on whether or not the appellate authority should have come down so heavily on SEBI, the fact cannot be gainsaid that there is perhaps merit in looking at what SEBI needs to do to prevent a recurrence of such observations. In matters involving alleged irregularities and/or misdemeanours, SEBI passes orders, normally through a WTM, who hears the case, and arrives at a decision. In other cases, matters are disposed of by Adjudicating Officers, who are appointed under Section 15 of the SEBI Act, and whose orders can then be appealed against before SAT.

As far as WTMs are concerned, a formal qualification in law, or experience in determining quasi-judicial matters, is not an essential qualification for appointment. The history of SEBI has shown that there have been WTMs whose rich experience prior to their appointment had nothing to do with quasi-judicial matters or even matters of administrative law. Suffice it to say that while they could have arrived at their conclusions based on robust common sense, and on hearing the party proceeded against, the articulation of this conclusions often left a lot to be desired, in the process leaving the doors of appellate opportunity wide open. Unless this is addressed, and persons with some understanding or experience of law are brought in as WTMs, well intentioned efforts could get grounded on technicalities or inadequate appreciation of what is material in the case to be decided.

Some years ago, discouraged by the number of SEBI’s orders that did not survive appellate scrutiny, the senior most functionary in the Ministry of Finance advised the then Chairman SEBI that it might be worthwhile to get the orders proposed to be passed by WTMs either vetted or redrafted by a retired Supreme Court judge. While this suggestion would have improved the quality of the final orders, it was decided to pass up the advice on the ground that outsourcing the writing of orders would be detrimental to the integrity of the process.

SEBI’s bigger problem would seem to lie in the area of adjudication. For many years, SEBI had quite a few Adjudicating Officers who were appointed as such because their services could not be gainfully utilised by the organisation in any of its several departments. It would have been futile to expect Adjudicating Officers, who were thus “parked”, to produce orders that would be able to hold their own in appellate fora. There have been instances where senior officials in SEBI were dismayed after reading some of these orders, and overcome with the helplessness that they could not intervene and correct matters, because the errors could be undone only by the Appellate Tribunal. The resultant transferred reputational risk to SEBI as an organisation because of ill-equipped Adjudicating Officers was a matter that SEBI learned to live with over the years.

There have been a few cases where persons with a legal background and appropriate legal experience have been posted as Adjudicating Officers. The difference in the quality of the orders passed by them, and by the legally untrained Adjudicating Officers, is perhaps a worthy subject for study. Halfway measures, such as putting the legally untrained persons through training programmes, do not travel far enough in producing officers who are equal to the task. Training, experience, attitude and formal qualifications should constitute the package on the basis of which Adjudicating Officers are chosen to discharge such onerous responsibilities.

There are jurisdictions, such as the USA, which select suitable persons for appointment as adjudicating authorities. They come to the assignment with knowledge and experience, and hence are able to arrive at reasoned conclusions that ordinarily survive appellate scrutiny. Sooner, rather than later, SEBI should travel down this path, and have a separately carved out adjudication branch, with persons selected from within or without, on the basis of their ability to deliver quality findings. Differently put, the positions of Adjudicating Officers should no longer be available as parking slots for inconvenient officers.

Capacity building should always be work-in-progress for organisations tasked with catering to public interest through determination of disputed issues. In addition to improving quality, it would reinforce the presumption, presently highly rebuttable, that adjudication is a separate branch, uninfluenced by departmental compulsions and directives.

Yet another initiative could be an audit of all the orders passed in the last few years by Adjudicating Officers. Common deficiencies and systemic shortcomings would then come to surface, rendering it easier for the organisation to put in place the necessary remedial measures. The building of public confidence in the instrumentality of adjudication is far too important a matter to be ignored any longer.

The recent past has shown us that even a Decision Review System (DRS) can be found fault with, and allegations made on the ground that it has been manipulated to serve the interest of one of the contending parties. It is therefore incumbent on all stakeholders of the system to ensure that the quality of first level orders is significantly improved, and references to the DRS become increasingly rare. Speed, clarity, continuity and consistency should be the building blocks of a system that seeks to deliver justice.

Postscript

Even as this piece was taking final shape, there was a news report that the Ministry of Finance was considering a statutory time limit for SEBI notices. Wouldn’t self-imposed discipline be a preferable alternative?

THE STORY SO FAR…

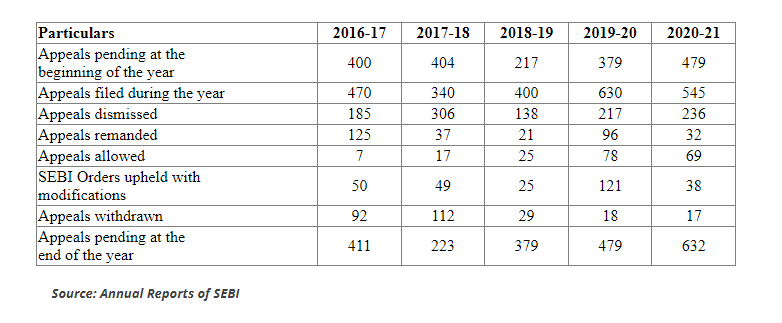

STATUS OF APPEALS BEFORE SAT

Do let us know of any specific issues you would like to see addressed in subsequent issues.

Excellence Enablers

Corporate Governance Specialists | Adding value, not ticking boxes | www.excellenceenablers.com

(292KB)

(292KB)